MASSAWA

EARLY HISTORY OF MASSAWA

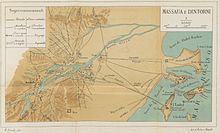

Historical map of Massawa

Massawa was originally a small seaside village, lying in lands coextensive with the

Kingdom of Axum also known as Kingdom of Zula in antiquity and overshadowed by the nearby port of

Adulis about 50 kilometres (31 mi) to the south.

[4]

The city reportedly has the

oldest mosque in

Africa, that is the

Mosque of the Companions (

Arabic:

مسجد الصحابة,

romanized: Masjid aṣ-Ṣaḥābah). It was reportedly built by

companions of Muhammad who escaped

persecution by Meccans.

[5] Following the fall of Axum in the 8th century, the area around Massawa and the town itself became occupied by the Umayyad Caliphate from 702 to 750

CE. The

Beja people would also come to rule within Massawa during the

Bajag Kingdom of Eritrea from the year 740 to the 14th century. Massawa was sited between the sultanates of

Qata,

Baqulin, and

Dahlak.

Midri-Bahri, an Eritrean kingdom (14th–19th centuries), gained leverage at various times and ruled over Massawa. The port city would also come under the supreme control of the Balaw people (people of Beja descent), during the Balaw Kingdom of Eritrea (12th–15th centuries). At this time, the

Sheikh Hanafi Mosque, one of the country's oldest mosque, was built on

Massawa Island, along with several other works of early Islamic architecture both in and around Massawa (including the

Dahlak Archipelago and the

Zula peninsula).

Main sights

Notable buildings in the city include the shrine of

Sahaba,

[13] as well as the 15th century Sheikh Hanafi Mosque and various houses of

coral. Many

Ottoman buildings survive, such as the local

bazaar. Later buildings include the Imperial Palace, built in 1872 to 1874 for

Werner Munzinger; St. Mary's Cathedral; and the 1920s Banco d'Italia. The Eritrean War of Independence is commemorated in a

memorial of three

tanks in the middle of Massawa.

MASSAWA: A FORGOTTEN GEM

EARLY HISTORY OF ADULIS

Pliny the Elder is the earliest writer to mention Adulis (N.H. 6.34). He misunderstood the name of the place, thinking the toponym meant that it had been founded by escaped

Egyptian slaves. Pliny further stated that it was the 'principal mart for the

Troglodytae and the people of

Aethiopia'. Adulis is also mentioned in the

Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a guide of the

Red Sea and the

Indian Ocean. The latter guide describes the settlement as an emporium for the

ivory, hides, slaves and other exports of the interior. It may have previously been known as

Berenice Panchrysos of the

Ptolemies. Roman merchants used the port in the second and third century AD.

Cosmas Indicopleustes records two inscriptions he found here in the 6th century: the first records how

Ptolemy Euergetes (247–222 BC) used

war elephants captured in the region to gain victories in his wars abroad; the second, known as the

Monumentum Adulitanum, was inscribed in the 27th year of a king of Axum, perhaps named Sembrouthes, boasting of his victories in Arabia and northern Ethiopia.

[2]

A fourth century work traditionally (but probably incorrectly) ascribed to the writer

Palladius of Galatia, relates the journey of an anonymous Egyptian lawyer (

scholasticus) to

India in order to investigate

Brahmin philosophy. He was accompanied part of the way by one Moise or Moses, the Bishop of Adulis.

Control of Adulis allowed Axum to be the major power on the

Red Sea. This port was the principal staging area for

Kaleb's invasion of the

Himyarite kingdom of

Dhu Nuwas around 520. While the scholar

Yuri Kobishchanov detailed a number of raids Aksumites made on the Arabian coast (the latest being in 702, when the port of

Jeddah was occupied), and argued that Adulis was later captured by the

Muslims, which brought to an end Axum's naval ability and contributed to the Aksumite Kingdom's isolation from the

Byzantine Empire and other traditional allies, the last years of Adulis are a mystery. Muslim writers occasionally mention both Adulis and the nearby

Dahlak Archipelago as places of exile. The evidence suggests that Axum maintained its access to the Red Sea, yet experienced a clear decline in its fortunes from the seventh century onwards. In any case, the sea power of Axum waned and security for the Red Sea fell on other shoulders.

No comments:

Post a Comment