History[edit]

Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian astronomer, mathematician, statistician, and sociologist, devised the basis of the BMI between 1830 and 1850 as he developed what he called "social physics".[3] Quetelet himself never intended for the index, then called the Quetelet Index, to be used as a means of medical assessment. Instead, it was a component of his study of l'homme moyen, or the average man

STATISTICAL INTERPRETION: Suppose we tried to fit a linear regression line of form

Y= A +B X

to the log (weights in grams) and log (heights in centimetres) for a random sample from a

specified population. Then the BMI would only be a reasonable summary if (1) a straight line

gives a good fit, and (2) he least squares estimates are close to A=0 and B=2. For some

populations, a totally different curve could be fit, It would be better to fit a bivariate distribution

to a bivariate scatterplot of log heights and log weights, Then the patient's data point

could be inserted on the diagram, and a professional assessment made, The bivariate normal

distribution may or may not give a good fit, I can see how Quetelet's suggestion is clearly

discriminatory against some populations,. He presumably knew that at the time.

If Y=A+B is a good least squares fit, then

BMI*= Weight/ [exp (A)X height to the power B}

is a reasonable index, which may be compared with percentiles for the population.

However other factors should also be taken into account

(Maybe the authors should have taken logs first. Their data may not be real)

Simple Linear Regression

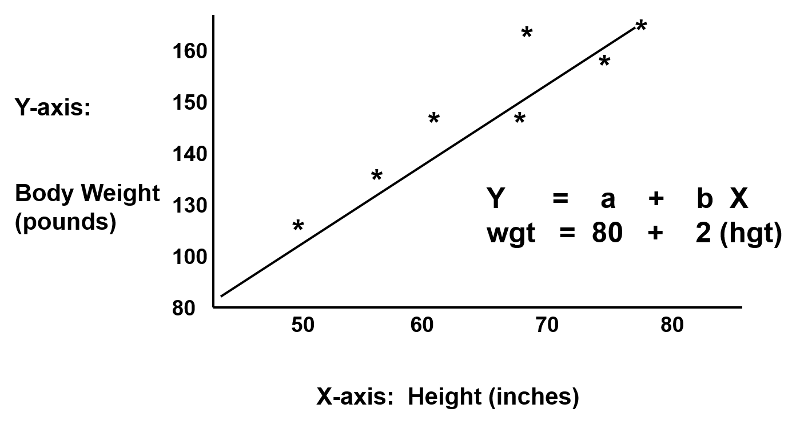

Regression analysis makes use of mathematical models to describe relationships. For example, suppose that height was the only determinant of body weight. If we were to plot height (the independent or 'predictor' variable) as a function of body weight (the dependent or 'outcome' variable), we might see a very linear relationship, as illustrated below.

We could also describe this relationship with the equation for a line, Y = a + b(x), where 'a' is the Y-intercept and 'b' is the slope of the line. We could use the equation to predict weight if we knew an individual's height. In this example, if an individual was 70 inches tall, we would predict his weight to be:

Weight = 80 + 2 x (70) = 220 lbs.

In this simple linear regression, we are examining the impact of one independent variable on the outcome. If height were the only determinant of body weight, we would expect that the points for individual subjects would lie close to the line. However, if there were other factors (independent variables) that influenced body weight besides height (e.g., age, calorie intake, and exercise level), we might expect that the points for individual subjects would be more loosely scattered around the line, since we are only taking height into account.

THE BIZARRE AND RACIST HISTORY OF THE BMI

Quetelet believed that the mathematical mean of a population was its ideal, and his desire to prove it resulted in the invention of the BMI, a way of quantifying l’homme moyen’s weight. Initially called Quetelet’s Index, Quetelet derived the formula based solely on the size and measurements of French and Scottish participants. That is, the Index was devised exclusively by and for white Western Europeans. By the turn of the next century, Quetelet’s l’homme moyen would be used as a measurement of fitness to parent, and as a scientific justification for eugenics — the systemic sterilization of disabled people, autistic people, immigrants, poor people, and people of color.

By 1985, the National Institutes of Health had revised their definition of “obesity” to be tied to individual patients’ BMIs. And with that, this perennially imperfect measurement was enshrined in U.S. public policy.

In 1998, the National Institutes of Health once again changed their definitions of “overweight” and “obese,” substantially lowering the threshold to be medically considered fat. CNN wrote that “Millions of Americans became ‘fat’ Wednesday — even if they didn’t gain a pound” — as the federal government adopted a controversial method for determining who is considered overweight.”

That second change paved the way for a new public health panic: the “Obesity Epidemic.” By the turn of the millennium, the BMI’s simple arithmetic had become a de rigeur part of doctor visits. Charts depicting startling spikes in Americans’ overall fatness took us by storm, all the while failing to acknowledge the changes in definition that, in large part, contributed to those spikes. At best, this failure in reporting is misleading. At worst, it stokes resentment against bodies that have already borne the blame for so much, and fuels medical mistreatment of fat patients.

No comments:

Post a Comment